Research Themes

Weather and Weathering

Weather is a product of both “the condition of the atmosphere at a given place and time” (noun), as well as the discourses and acts of “passing through and surviving” (transitive verb), or weathering.

In the contemporary sense, “weathering” underscores lived experiences of climate change and extreme weather events, and counters the linear and inhuman narratives of climate change confined within scientific graphs and mathematical models.

In historicising “weathering”, we see that while scientists and officials sought to measure temperature and rainfall, predict tropical storms, and classify climatic conditions, people’s actual experiences of these natural and physical forces were deeply personal and culturally specific.

This research is particularly relevant today, given the unequal impacts of our current climate crisis on different communities.

“By the sweat of my brow I tried to be mistaken for a shaheb but still that man called me Baboo.”

Gaganendranath Tagore, Adbhut Lok (Realm of the Absurd), 1917

Bodies and Sources

Weather and seasons not just defined scientific and social viewpoints, modes of cultural activity, the clothes people wore, the foods they ate, the architecture and layouts of urban and domestic spaces, but were also defined by how and what people felt when they sweat in the heat and humidity, were drenched in the rain, or caught in a storm.

Finding historical records of the embodied experiences of weather and seasons, and the interconnected social, political, cultural and scientific lives of people requires examining echoes and shadows in alternative sources — satire, cartoons, commentary, complaints, folklore — that foreground the sensory and affective ways in which people experienced and interpreted weather.

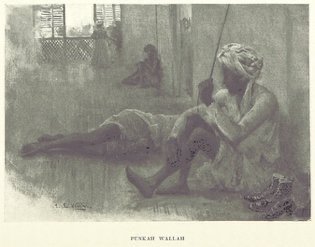

“Punkah Wallah”

Edwin Lord Weeks, From the Black Sea through Persia and India (1896), p.399

Knowledge and Scale

Historicising the sociological and anthropological concept of “weathering” helps us examine how processes of weathering and experiences of weather — including the knowledge of seasons, clothing, nutrition, and the design, layout and use of public and domestic spaces — both drew from, and were embedded in the creation and maintenance of racial, colonial and social thinking and practices.

It also helps us reconcile the different scalar, temporal and cultural boundaries that climate, seasons and weather permeate, and extend historical writings influenced by the planetary scale of environmental and climatic complexities, and the anxieties of global crises prompted by threats introduced by the spectre of the Anthropocene.

“Bombay tram-horse wearing horse-cap”

Beast and Man in India, by John Lockwood Kipling (1891), p.206